Dr. Kristen Rex gave Arizona third grade postcard contest awards to two students and writes, "They say lightning doesn’t strike the same place twice but at Benson primary school…it hit big! Both Harper and Mika celebrated their class pizza parties together after winning this year‘s postcard contest. Families came out, the press was there to record the event, and a great time was had by all!"

published by the Historical League, Inc.

2018

Volume I 2007 Regional winner of the Tabasco Community Cookbook award

Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Skyler James: winner of 3rd grade postcard contest

The latest 3rd grader to celebrate her win of the Arizona Postcard Contest is Skyler James. Along with her family, her teacher and classroom, they all enjoyed a pizza party and fun swag. (check out the cute teddy bear). We are appreciative of her creative artwork which has been made into postcards and can be found at AHS museums.

Monday, April 28, 2025

Third grade postcard winner Andy Zhao

The Marana school newspaper writes, "We are thrilled to announce that Andy Zhao, a talented third grader at our school, has been selected as a winner of the Arizona Historical Society Museum's Postcard Contest! Andy’s artistic design stood out among many entries from students across the state, earning him this prestigious recognition."

Sunday, April 27, 2025

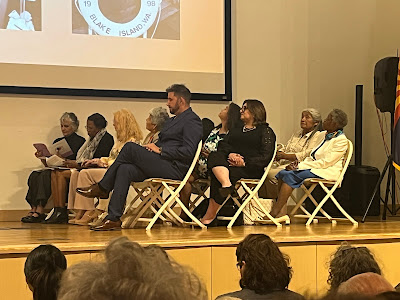

Arizona Women's Hall of Fame honorees

Congratulations to nine very deserving women who were inducted into the 2025 Arizona Women's Hall of Fame at Arizona Heritage Center at Papago Park. Historical Leagues own member Dr. Josephine Pete was one of the honorees. The bios tell the story of their many accomplishments!

Congratulations to nine very deserving women who were inducted into the 2025 Arizona Women's Hall of Fame at Arizona Heritage Center at Papago Park. Historical Leagues own member Dr. Josephine Pete was one of the honorees. The bios tell the story of their many accomplishments!

Thanks to Historical League members who have been a big part of the Hall of Fame committee: Norma Jean Coulter and Zona Lorig.

Saturday, April 26, 2025

Arizona Women's Hall of Fame inductee Dr. Josephine Pete

Wonderful Event: Arizona Women's Hall of Fame honored 9 new inductees with Brownie troops watching, leading the Pledge of Allegiance and fascinated with the program. Historical League member Dr. Josephine Pete was one of the honorees. Thanks to Norma Jean Coulter for the great photos and all her work with this program.

Surrounded by family, friends, and fellow Historical League members, Dr. Josephine Pete received a well-deserved honor. Check out her biography.

|

| Norma Jean Coulter and honoree Dr. Josephine Pete |

|

| Pam den Draak, Carolyn Mendoza, Zona Lorig, Linda Fritsch |

|

| Cathy Shumard, Carolyn Mendoza, Margaret Baker. Other Historical League members not pictured were Laurie-Sue Retts, Susan Dale, Katie Tovar, Sharon McKinney and Anne Lupica. |

Friday, April 25, 2025

Third Grade Postcard Contest

To help celebrate Arizona’s birthday a postcard making contest was created for 3rd graders by Dr. Kristen Rex. Lessons and activities were developed to support teachers’ needs to meet 3rd grade state standards on Arizona history. Over 2,000 students have participated to date, 700 postcard art pieces are scored for creativity, accuracy in art and social studies, and 6 postcards are selected as winners. Winning students earned their class a pizza party, swag bag, and their teachers a year’s membership to the Arizona Historical Society.

Dr. Rex organizes this program and she travels the state, hand delivering the awards to each student and celebrating with the classroom.

What a great way to learn about Arizona history. The students get involved and perhaps continue with the National History Day Arizona program.

|

| Kate from Huachucha Mountain Elementary School 2025 with Dr. Rex |

Wednesday, April 23, 2025

The Many Volunteers at NHDAZ State Competition

Smiling faces greeted the students for NHDAZ State Competition at the check in table at South Mountain Community College April 11. Thanks to Historical League volunteers Robin Ferguson, Melissa Johnson, Margaret Baker and Pam denDraak for helping make the day go smoothly. There were a total of fourteen Historical League members helping as judges, greeters, photographers and with whatever needed to be done.

Monday, April 21, 2025

Arizona Postcard winner Wyatt at Lineweaver Elementary, Tucson

Congrats to Wyatt for for winning a pizza party! Looks like Wyatt got some swag also! His family and classroom at Lineweaver Elementary in Tucson enjoyed the event. He was a winner in the Arizona 3rd grade postcard contest learning all about Arizona in the process.

Wyatt‘s mom happens to be a principal in Sunnyside school District so perhaps we will get a few more entries next year.